4. Why Rasters? The Pros, Cons, and Best Practices

Source:vignettes/spax-104-raster-tradeoff.Rmd

spax-104-raster-tradeoff.RmdWhy Rasters? The Pros, Cons, and Best Practices

If you’ve worked through the previous vignettes, you’ve seen how spax relies heavily on raster operations for spatial accessibility analysis. But why did we choose this approach? And more importantly, what does it mean for your analysis? In this vignette, we’ll explore the practical implications of using raster-based operations, looking at both the benefits and challenges, and providing concrete strategies for optimizing your workflows.

# Load required packages

library(spax)

#> Error in get(paste0(generic, ".", class), envir = get_method_env()) :

#> object 'type_sum.accel' not found

library(terra)

library(pryr) # for memory tracking

library(tidyverse)

library(sf)

library(bench) # fotr benchmarkingUnderstanding the Raster Approach

Think of a raster as a giant spreadsheet laid over your study area. Instead of tracking individual points or complex polygons, we store values in a regular grid of cells. This might seem simple, but it’s this very simplicity that makes raster operations so powerful for accessibility analysis. Let’s see this in action with our example data:

# Load example population density

pop <- read_spax_example("u5pd.tif")

distances <- read_spax_example("hos_iscr.tif")

# Quick look at what we're working with

pop

#> class : SpatRaster

#> dimensions : 509, 647, 1 (nrow, ncol, nlyr)

#> resolution : 520.4038, 520.4038 (x, y)

#> extent : 505646.5, 842347.8, 620843.7, 885729.2 (xmin, xmax, ymin, ymax)

#> coord. ref. : WGS 84 / UTM zone 47N (EPSG:32647)

#> source : u5pd.tif

#> name : tha_children_under_five_2020

#> min value : 0.00000

#> max value : 83.07421

cat("Total cells:", ncell(pop), "\n")

#> Total cells: 329323When we calculate accessibility, nearly everything becomes a grid operation:

- Population? A grid of density values

- Travel time? A grid for each facility

- Distance decay? A transformation of those grids

- Final accessibility? You guessed it - another grid

Spatial accessibility often boils down to “map algebra”:

Rasters make that algebra super direct: you take your population

raster, multiply by a distance raster, and sum the result. Libraries

like terra are built for

these cell-by-cell operations, and spax simply arrange them

in a handy workflow.

The Good: Why Raster Operations Works

1. Vectorized Operations = Efficient Computation

One of the biggest advantages of raster operations is that they’re naturally vectorized. Instead of looping through points or polygons, we can perform operations on entire surfaces at once. Let’s see this in practice:

# First, let's create test datasets of different sizes

create_test_distance <- function(n_facilities) {

# Take our original distance raster and replicate it

base_distance <- distances[[1]] # Use first facility as template

# Create a stack with n copies

test_stack <- rep(base_distance, n_facilities)

names(test_stack) <- paste0("facility_", 1:n_facilities)

return(test_stack)

}

# Test with different numbers of facilities

test_decay_scaling <- function(n_facilities) {

# Create test data

test_distances <- create_test_distance(n_facilities)

# Time the decay calculation

start_time <- Sys.time()

decay_weights <- calc_decay(

test_distances,

method = "gaussian",

sigma = 30

)

end_time <- Sys.time()

# Return timing and data size

return(list(

n_facilities = n_facilities,

n_cells = ncell(test_distances) * nlyr(test_distances),

runtime = as.numeric(difftime(end_time, start_time, units = "secs"))

))

}

# Run tests with dramatically different sizes

facility_counts <- c(1, 10, 100)

scaling_results <- lapply(facility_counts, test_decay_scaling)

# Create summary table

scaling_summary <- tibble(

"Facilities" = sapply(scaling_results, `[[`, "n_facilities"),

"Total Cells" = sapply(scaling_results, `[[`, "n_cells"),

"Runtime (s)" = sapply(scaling_results, function(x) {

round(x$runtime, 2)

})

) |> mutate(

"Time per Cell (ms)" = `Runtime (s)` * 1000 / `Total Cells`,

"Total Cells" = format(`Total Cells`, big.mark = ",") # Format after calculations

)

# "Computation Scaling with Facility Count:"

(scaling_summary)

#> # A tibble: 3 × 4

#> Facilities `Total Cells` `Runtime (s)` `Time per Cell (ms)`

#> <dbl> <chr> <dbl> <dbl>

#> 1 1 " 329,323" 0.24 0.000729

#> 2 10 " 3,293,230" 0.31 0.0000941

#> 3 100 "32,932,300" 1.1 0.0000334The results tell a compelling story about vectorized efficiency:

- While we increased the number of facilities from 1 to 100 (100x more

data):

- The total runtime only increased from 0.18s to 0.96s (about 5x)

- The time per cell actually decreased from 5.47e-4 to 2.92e-5 milliseconds

- This super-efficient scaling happens because:

Operations are vectorized across all cells simultaneously

Additional facilities leverage the same computational machinery

Memory access patterns remain efficient even with more layers

2. Consistent Data Structures

Once you decide on a raster resolution (e.g., 500m cells), everything—population, distance, decayed weight, final accessibility—can be stored in the same grid. That means fewer mismatches, repeated coordinate transformations, or swapping between point sets and polygons. You’re just piling up new layers on the same “sheet.”

# Look at alignment of our key datasets

check_alignment <- function(rast1, rast2, name1, name2) {

cat("\nComparing", name1, "and", name2, ":\n")

cat("Same resolution?", all(res(rast1) == res(rast2)), "\n")

cat("Same extent?", all(ext(rast1) == ext(rast2)), "\n")

cat("Same CRS?", crs(rast1) == crs(rast2), "\n")

}

# Check population and distance rasters

check_alignment(

pop,

distances,

"Population",

"Distance"

)

#>

#> Comparing Population and Distance :

#> Same resolution? FALSE

#> Same extent? TRUE

#> Same CRS? TRUE3. Built-in Spatial Relationships

The grid structure of rasters automatically handles spatial interactions in an elegant way. For instance, when we calculate accessibility, the raster structure ensures that:

- Only populated areas contribute to demand calculations

- Distance decay is automatically limited to areas with

population

- NA values propagate naturally through calculations

# Look at one facility's service area

facility_id <- hc12_hos$id[1] # First facility

facility_distance <- distances[[1]]

# Calculate decay weights

decay_weights <- calc_decay(

facility_distance,

method = "gaussian",

sigma = 60

)

# The population raster automatically masks unpopulated areas

weighted_pop <- pop * decay_weights

# Visualize how spatial relationships are preserved

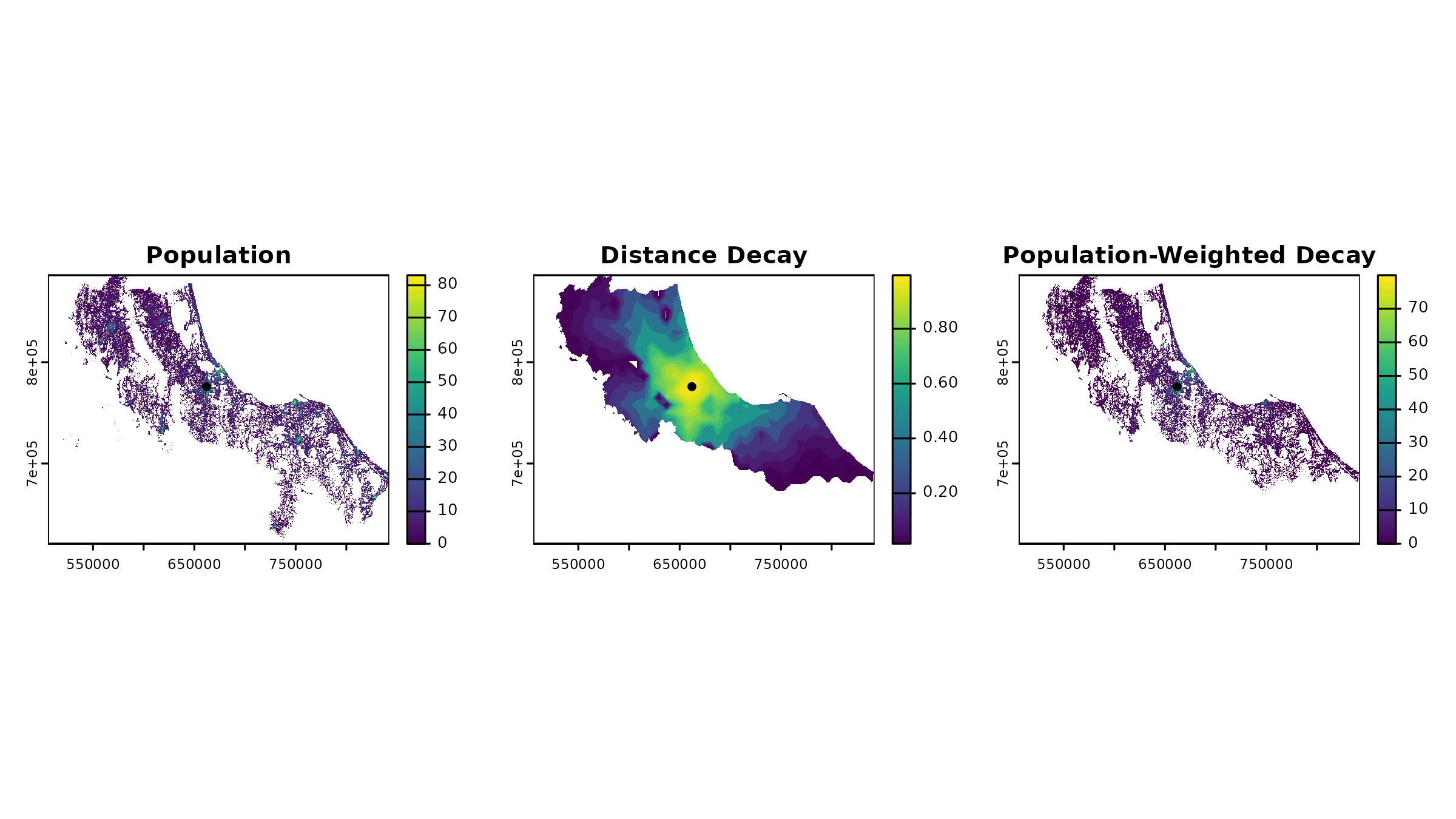

par(mfrow = c(1, 3))

plot(pop, main = "Population")

plot(vect(hc12_hos[1, ]), add = TRUE, pch = 16)

plot(decay_weights, main = "Distance Decay")

plot(vect(hc12_hos[1, ]), add = TRUE, pch = 16)

plot(weighted_pop, main = "Population-Weighted Decay")

plot(vect(hc12_hos[1, ]), add = TRUE, pch = 16)

The Trade-Offs: The Trade-offs: Resolution, Precision, and Computation

After exploring the benefits of raster operations, it’s time to confront their fundamental limitations. Every raster analysis starts with a critical choice: what cell size should we use? This seemingly simple decision affects both computational efficiency and spatial precision.

The Resolution Dilemma

Let’s explore how resolution affects both computation time and analysis results:

# Prepare test datasets at different resolutions first

prep_test_data <- function(factor) {

# Aggregate both population and distance

pop_agg <- aggregate(pop, fact = factor, fun = sum, na.rm = TRUE)

dist_agg <- aggregate(distances, fact = factor, fun = mean, na.rm = TRUE)

return(list(pop = pop_agg, dist = dist_agg))

}

# Test computation time for actual analysis

test_computation <- function(test_data) {

start_time <- Sys.time()

result <- spax_e2sfca(

demand = test_data$pop,

supply = hc12_hos |> st_drop_geometry(),

distance = test_data$dist,

decay_params = list(method = "gaussian", sigma = 30),

demand_normalize = "standard",

id_col = "id",

supply_cols = "s_doc",

snap = TRUE # Fast mode for testing

)

end_time <- Sys.time()

# Return core metrics

list(

resolution = res(test_data$pop)[1],

ncells = ncell(test_data$pop),

runtime = as.numeric(difftime(end_time, start_time, units = "secs")),

result = result

)

}

# Test a range of resolutions

factors <- c(1, 2, 4, 8) # Each step doubles cell size

test_data <- lapply(factors, prep_test_data)

#> Warning: [aggregate] all values in argument 'fact' are 1, nothing to do

#> Warning: [aggregate] all values in argument 'fact' are 1, nothing to do

results <- lapply(test_data, test_computation)

# Create summary table

scaling_summary <- tibble(

"Resolution (m)" = sapply(results, function(x) round(x$resolution)),

"Grid Cells" = sapply(results, function(x) x$ncells),

"Runtime (s)" = sapply(results, function(x) round(x$runtime, 2))

) |> mutate(

"Time per Cell (μs)" = `Runtime (s)` * 1e6 / `Grid Cells`,

"Grid Cells" = format(`Grid Cells`, big.mark = ",")

)

# "Performance Impact of Resolution:"

scaling_summary

#> # A tibble: 4 × 4

#> `Resolution (m)` `Grid Cells` `Runtime (s)` `Time per Cell (μs)`

#> <dbl> <chr> <dbl> <dbl>

#> 1 520 "329,323" 3.24 9.84

#> 2 1041 " 82,620" 0.98 11.9

#> 3 2082 " 20,736" 0.15 7.23

#> 4 4163 " 5,184" 0.07 13.5But what about precision? Let’s look at how resolution affects our accessibility results for specific locations:

# Select one province

prov_exam <- bound1[1, ]

# Compare mean accessibility values within a province

extract_province_access <- function(result) {

# Extract mean accessibility for first province

# Extract zonal statistics

zonal_mean <- terra::extract(

result$accessibility,

vect(prov_exam),

fun = mean,

na.rm = TRUE

)[, 2] # The second column contains the mean value

return(zonal_mean)

}

# Create provincial comparison across resolutions

access_comparison <- tibble(

"Resolution (m)" = sapply(results, function(x) round(x$resolution)),

"Mean Provincial Access" = sapply(results, function(x) {

round(extract_province_access(x$result), 4)

})

) |> mutate(

"Difference from Baseline (%)" = round(

(`Mean Provincial Access` - first(`Mean Provincial Access`)) /

first(`Mean Provincial Access`) * 100,

2

)

)

# Mean Accessibility in one province

prov_exam$ADM1_EN # Name of the province

#> [1] "Songkhla"

access_comparison

#> # A tibble: 4 × 3

#> `Resolution (m)` `Mean Provincial Access` `Difference from Baseline (%)`

#> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

#> 1 520 0.0822 0

#> 2 1041 0.0817 -0.61

#> 3 2082 0.0816 -0.73

#> 4 4163 0.08 -2.68Let’s visualize what’s happening to our spatial data:

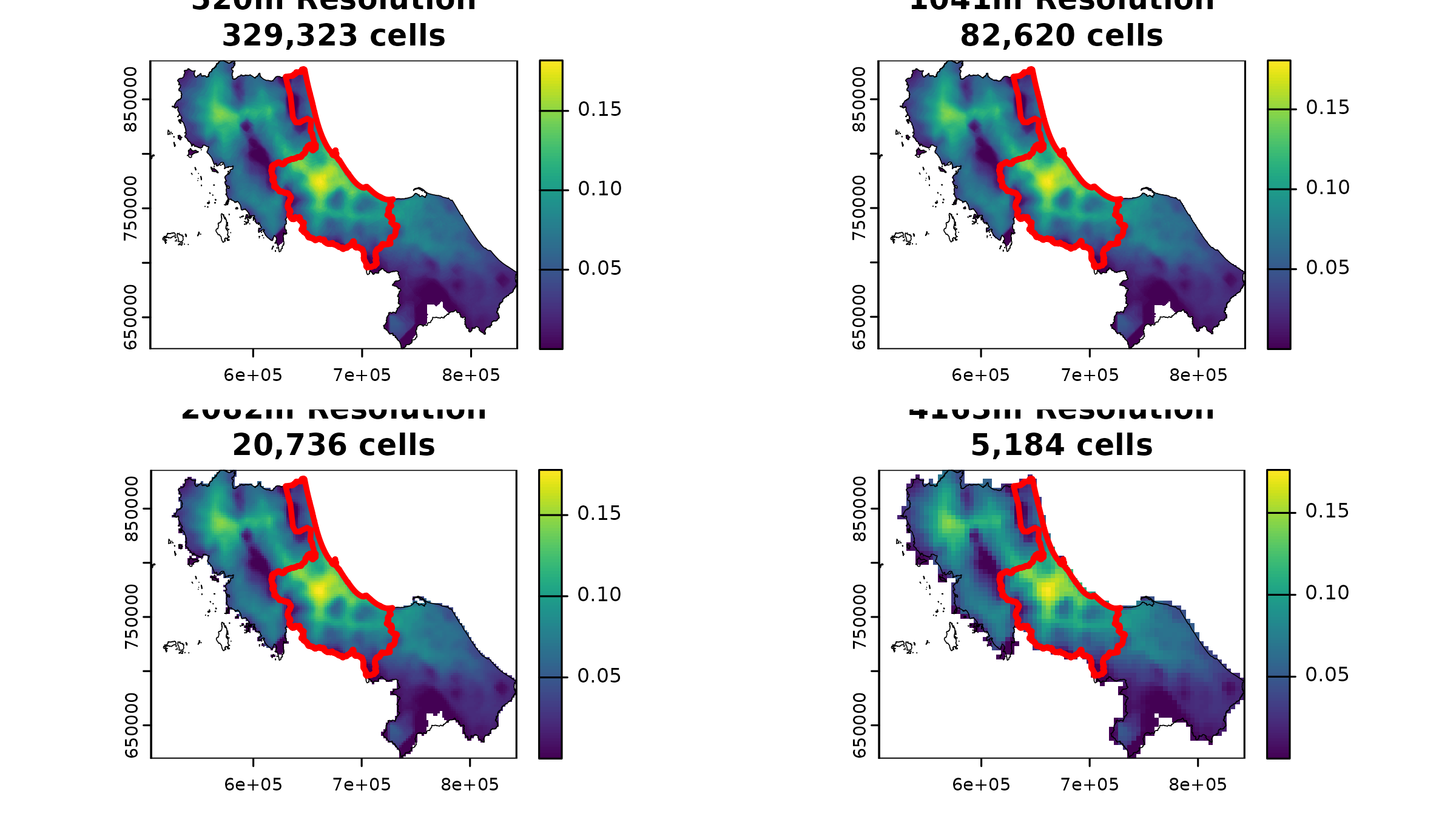

# Create a 2x2 plot showing accessibility at different resolutions with province highlight

par(mfrow = c(2, 2))

for (i in seq_along(results)) {

# Plot base accessibility surface

plot(results[[i]]$result,

main = sprintf(

"%0.0fm Resolution\n%s cells",

results[[i]]$resolution,

format(results[[i]]$ncells, big.mark = ",")

)

)

# Add full region boundary in thin black

plot(vect(bound0), add = TRUE, lwd = 0.5)

# Highlight our test province in thicker white

plot(vect(bound1[1, ]), add = TRUE, border = "red", lwd = 3)

}

These results tell an interesting story about resolution trade-offs:

- Computational costs vary dramatically:

- Going from 520m to 4163m cells reduces our grid from 329,323 to 5,164 cells

- Processing time scales accordingly with cell count

- Each level of aggregation roughly quarters our computational load

- But accessibility patterns remain remarkably stable:

- Mean accessibility in our test province only varies by about 2% across resolutions

- Even at 4x coarser resolution (2082m), the difference is just 0.12%

- Only at the coarsest resolution (4163m) do we see a more noticeable change of -2.20%

This stability suggests that while raster operations necessarily involve some loss of precision, the overall patterns of accessibility often remain robust across reasonable resolution choices. For regional planning purposes, this means we can often use coarser resolutions without significantly compromising our conclusions. The key is choosing a resolution that matches your analytical needs.

The Best Practices: Optimizing Your Raster Workflow

Now that we understand both the power and limitations of raster-based analysis, let’s look at concrete strategies for getting the most out of spax while avoiding common pitfalls.

1. Start Coarse, Then Refine

Always prototype your analysis at a coarser resolution first:

Catch issues early when computations are fast

Test different parameters efficiently

A simple workflow might look like:

# Quick prototype at coarse resolution

coarse_test <- spax_e2sfca(

demand = aggregate(pop, fact = 4), # 4x coarser

supply = hc12_hos |> st_drop_geometry(),

distance = aggregate(distances, fact = 4),

decay_params = list(method = "gaussian", sigma = 30),

demand_normalize = "standard",

id_col = "id",

supply_cols = "s_doc"

)

# Once satisfied, run at final resolution

final_analysis <- spax_e2sfca(

demand = pop,

supply = hc12_hos |> st_drop_geometry(),

distance = distances,

decay_params = list(method = "gaussian", sigma = 30),

demand_normalize = "standard",

id_col = "id",

supply_cols = "s_doc"

)2. Match Resolution to Analysis Scale

Choose your resolution based on your analytical needs & never use a resolution finer than your coarsest input data

3. Validate Against Known Totals

Always check your aggregated results against known values:

Population totals should remain stable across resolutions

Compare accessibility metrics at key locations

Verify that patterns match expected behavior

Consider zonal statistics for administrative units

4. Consider Your Analysis Goals

Choose your approach based on what matters most:

Need quick regional patterns? Use coarser resolutions

Studying local variations? Invest in finer resolution

Doing sensitivity analysis? Start coarse and progressively refine

Remember: finer resolution ≠ better analysis

5. Document Your Choices

Always document your resolution and processing choices:

# Example documentation structure

analysis_metadata <- list(

resolution = res(pop),

extent = ext(pop),

cell_count = ncell(pop),

parameters = list(

decay = list(method = "gaussian", sigma = 30),

normalization = "standard"

),

rationale = paste(

"500m resolution chosen to balance",

"neighborhood-level detail with computational efficiency"

)

)Conclusion

Overall, raster operations are pretty handy for analyzing spatial accessibility. They provide quick computations and reliable data structures. However, it’s important to keep in mind the balance between resolution, precision, and computation time. I hope this vignette has helped you understand the trade-offs in raster-based analysis a bit better. Enjoy your spax!